Believing in Rain with Stephen Bridgehouse and Richard Ullmann

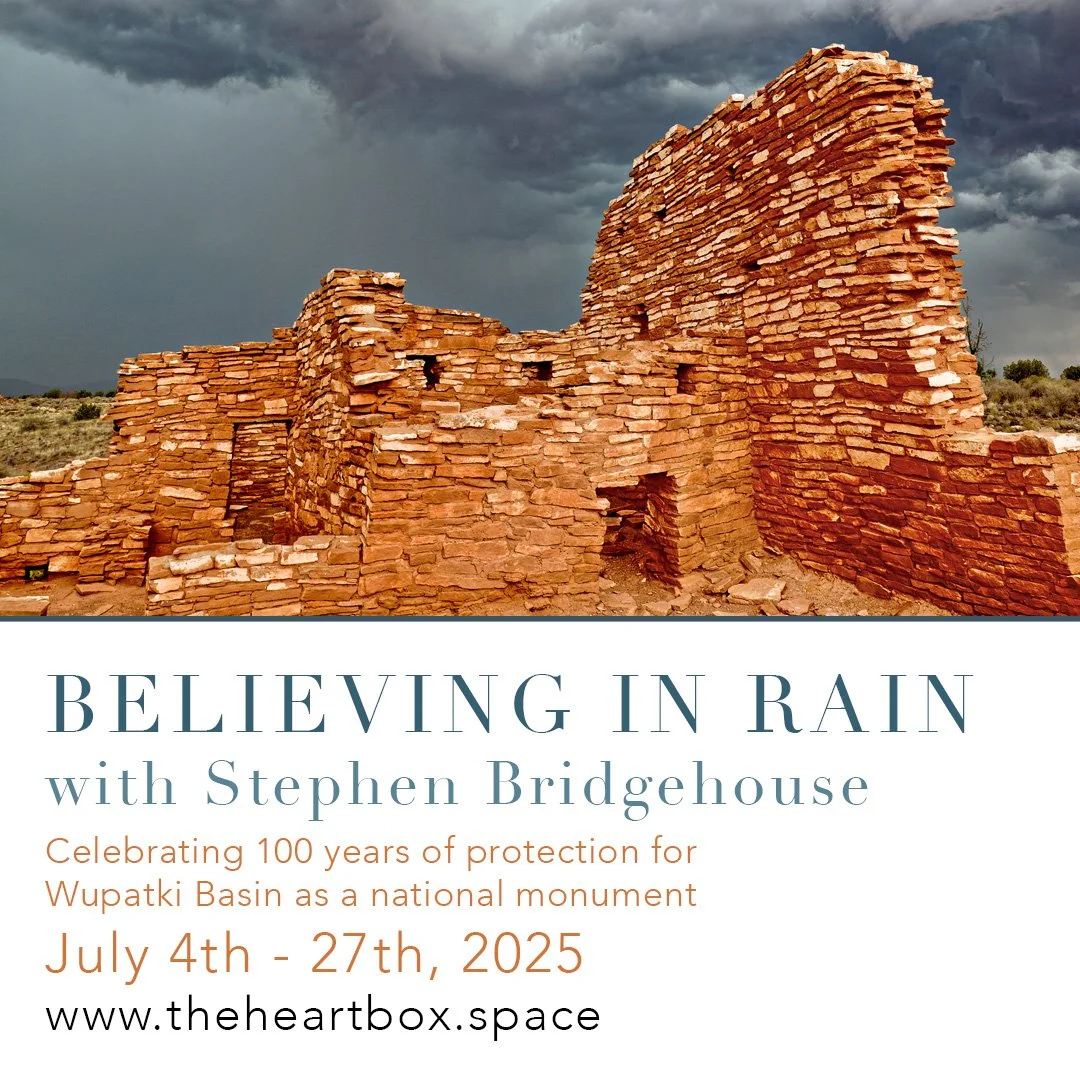

Believing in Rain is a striking photographic exhibition by Stephen Bridgehouse, born from his artist residency with Wupatki National Monument and shared with the public through The HeArt Box during the month of July, a time of waiting and calling in the rain in Northern Arizona.

Believing in Rain celebrates a century of protection for Wupatki Basin as a national monument. This photo documentary is a collaboration between ancestral builders; the passage of time reshaping their structures; the ever-changing sky over the arid basin, and a camera in the hands of Stephen Bridgehouse. The captured images bring unique atmospheric moments and landscapes of Wupatki into downtown Flagstaff.

Believing in Rain with Stephen Bridgehouse, July 4th - 27th, 2025

Stephen Bridgehouse who has spent decades in the southwest, created "Believing in Rain," a photographic documentary celebrating Wupatki Basin's century of protection as a national monument. Through his photography and passion, he captures atmospheric moments and landscapes of Wupatki over a two-year period, reflecting on the historical significance of the area and the traditions of its ancestral builders. He emphasizes the importance of observing nature, particularly the clouds, and the need to protect sacred places.

This exhibition is in collaboration with Wupatki National Monument with the support of Western National Parks (WNP), a nonprofit education partner of the National Park Service. WNP supports parks across the West, developing products, services, and programs that enhance the visitor experience, understanding, and appreciation of national parks.

A few questions asked to Stephen Bridgehouse, Photographer of Believing in Rain

What was the spark in you to create this series? What drew you to Wupatki?

The history and the people of the Southwest have been an interest of mine as long as I can remember. I am from El Paso, and I think borderland communities especially have long been at a crossroads for asking deeper questions of identity and place. Pueblo people are a constant in this land, and even non-native people like myself hold onto this continuity as if it is a tether tied to something immoveable. Despite all of these ancient communities we can consider today, the entire story has been left out of American history. Modern Pueblo people allow the National Park Service to be stewards of these places and to tell the story. The generosity they share with us inspires me to share with others as well. I hope that my photographs present the villages and landscape in the best light possible. Nothing here is my creation. I photographed what I found like anyone can. I wish I could safely sew up all the open pit mines or ensure that native people have safe water to drink, but I am just a photographer. We are each responsible for kindling the spark of activism on behalf of our neighbors. Personally, I was drawn to the villages of Wupatki first as a tourist, then as a ranger, before becoming an artist in residence.

What did you learn or stood out to you as a moment of wisdom from this project?

The structures we see at Wupatki, Lomaki, Wukoki and Citadel are substantial. They were centers in their time and were well known far and wide. They were gathering places for people who lived rurally. They were trade centers where several languages were understood. Macaws were bred; games were played; and knowledge was shared. Today, there are many stories that feature these villages, and the stories have been shared orally to teach at Hopi and Zuni for many centuries. My awareness of these communities has grown from spending time in these places, and it is reinforced by the Park visitors who report that they feel the presence of people or they hear the sound of drumming when they visit these places. What stands out to me most is continuity. We may all desire to be safe in a place we can call home forever. I ask myself, are the mountains and mesas really sacred to me? What is my relationship to the rains and the rivers and the plains? When I say I love a canyon…what am I really trying to say? When the people who have called this place home for many thousands of years speak in their languages, their words are understood. They speak with a wisdom of space that leaves me envious. Residents in the Southwest can benefit a great deal by behaving like a community while listening to our neighbors. This project has taught me to ask how we can genuinely treat one another as neighbors, to see one another honestly in times of trial and need.

Have you always had this relationship with the sky, the clouds? What do you find so inspiring about the sky?

The Earth-ling it seems is always looking up! There is so much out there and above. Day or night, there is so much change occurring. After all these years, our Moon appears to suddenly be in a phase I haven’t noticed before. Now it seems so different than just a few weeks ago. Just when I learn a new constellation, it’s gone, and now what is all this? I was sure the clouds were moving from right to left, but I see now the opposite. There was no rain in the forecast, but half an inch just fell and the birds are singing like mad. All this while the speeding planet hurtles along its course at unknowable speed. It’s unlikely that I will blast off in a rocket, but this place we share will fill me with questions, and I will watch from here while considering them. Mine is a daydreamer’s life, I suppose, watching always what the clouds are up to and where they are off to and what they might do along the way. Having spent my life in the Southwest, I learned quickly the value of the cloud overhead. Cloud cover moves everything in the right direction. As long as I can remember, people have prayed for the clouds and rain. I am sure I have watched the sky from the beginning.

How does your photography and your other work as a park ranger feed each other?

It has always been a great privilege to work as a ranger. Everything I have and everything I am has come from this work. The same could be said for many pastimes and many occupations, but creating quality work over a lifetime takes both time and effort. Success can manifest in many different ways, but the best feeling comes when I am able to help someone see something they know to be true in a very different way. The changing mind! Photography is an art that changes my mind. It is no easy task to turn the familiar into something new. While I don’t produce photography in my role as a ranger, my work drives me outside the rest of the time, and this liberates me. This is the space where art happens. In some ways, the two are complementary, and in others…unrelated.

Being someone who works so closely with our public lands I am sure you see so much that others do not. If there is any wisdom or nugget of truth you could share with the public, what would it be?

Working at Mesa Verde, Hovenweep, Wupatki, and on Cedar Mesa, there is always one perception the public has that is impossible to shake. Non-Natives look on the indigenous people of the past as unsophisticated and primitive, even when they are presented with strong evidence of the contrary. Rather than consider a people’s ability to thrive as dry-land farmers on the parched plains of Wupatki for many generations, it is the people’s ability to build masonry walls that creates awe. The superiority complex is real and is applied everyday. Everyone, everywhere, throughout time has used what they’ve had to get what they needed, and this is something we all have in common. Discovering what we have in common is a far better use of time than dividing and dissecting so that we can place space between ourselves and the ancestors.

Artist talk with Stephen Bridgehouse, July 4th, 2025

A few questions asked to Richard Ullmann of Wupatki National Park

How do you see the relationship with artists and national parks working together? Is there a benefit for both?

Any good relationship should be beneficial for all parties! National Parks benefit by creative interpretation of place and in public interface/ engaging visitors in their public lands; artists ideally are inspired to create by the natural and cultural landscapes they interpret through their work.

With celebrating Wupatki’s 100 year centennial, how has this park/monument helped bridge relationships between indigenous people of this place and the surrounding visitors that come there?

Associated Tribes - Wupatki National Monument (U.S. National Park Service) has excellent perspective on what you ask here. Copy/paste from a portion of that site: "The entire region that includes the Flagstaff Area National Monuments has been home to Native people since time immemorial.

The Flagstaff Area National Monuments (Walnut Canyon, Sunset Crater Volcano, and Wupatki) are places of immeasurable importance to Native peoples in the Southwest. Wupatki shares boundaries with the Navajo Nation, and a total of thirteen federally recognized tribes are traditionally associated with the Monuments. Park staff have been working with tribal people for many years and are creating ever-better collaborative tribal partnerships.

We gratefully acknowledge the Native peoples on whose ancestral homelands we gather, as well as the diverse and vibrant Native communities who continue to make their home here today.

As we celebrate Native heritage, please take a moment to ponder and appreciate the diverse cultural stories these lands hold. This history, played out on lands including the Flagstaff Area National Monuments, has been dramatic and difficult - but learning from the past can help us all in the future."

Is there one thing you could share about Wupatki that you think everyone should know? Or something that is so valuable about this place?

Wupatki is a very special place to many different people over a very long time period. As such, thank you for being respectful when you visit and hope you feel the immense amount of history and time represented there.

How important is it to protect these places? Public lands and parks

I love that oft-used Wallace Stegner quote of "National parks are the best idea we ever had. Absolutely American, absolutely democratic, they reflect us at our best rather than our worst." As such, I would argue there is great value and importance in protecting public lands to include our National Park system.

Can you share more about the artist in residency program? Something you are proud of?

Grateful that the Flagstaff Area National Monuments has capacity to have an 'appropriately sized' Artist-in-Residence program, and hope to continue to nurture this program given the amazing and creative mutually-beneficial collaborations that have come out of this program so far!